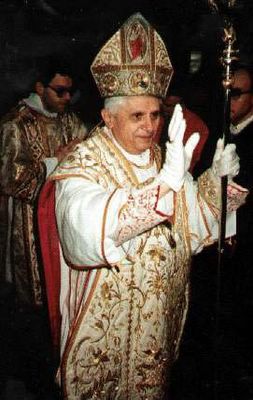

No primeiro sermão que proferiu, o Santo Padre Bento XVI anunciou aquelas que serão as prioridades do seu pontificado, entre as quais saliento a proposta de releitura do Concílio Vaticano II, a ser feita em fiel continuidade com a bimilenar tradição da Igreja, a que também fez expressa referência.

Por esta razão, parece-me que devem os católicos tradicionais dar um amplo benefício da dúvida ao actual Papa, e sem caírem em ingenuidades desnecessárias, não cavarem de imediato um fosso intransponível com Roma, através do relembrar de antigos pronunciamentos de pendor modernista do então Cardeal Ratzinger, a que o próprio parece já ter renunciado, para mais numa altura em que as potências infernais, gravemente feridas com o resultado do último conclave, assestam a totalidade da sua fúria sobre a figura do Romano Pontífice.

Na minha estrita opinião pessoal, que não vincula nada nem ninguém, Joseph Ratzinger foi um dos melhores amigos que a tradição teve em Roma durante o pontificado de João Paulo II; ora, considerando a devoção que o agora Papa Bento XVI nutre pela Missa de rito latino-gregoriano; com a intercessão da Santíssima Mãe de Deus, e a oração intensa dos fiéis da tradição; bem como com a mais terrena e prestimosa colaboração do Cardeal Castrillón Hoyos, na Comissão Ecclesia Dei; acredito que estarão reunidas as condições para que a Missa Tridentina possa ser libertada com celeridade dos entraves modernistas que correntemente a tolhem.

De resto, em face do pensamento que o presente Papa plasmou no seu livro "The Spirit of Liturgy" (desconheço se existe tradução portuguesa), de que em seguida se transcrevem alguns trechos), é pelo menos legítimo ter a esperança de que tal possa suceder:

- In the early Church, prayer towards the east was regarded as an apostolic tradition. We cannot date exactly when this turn to the east, the diverting of the gaze from the Temple, took place, but it is certain that it goes back to the earliest times and was always regarded as an essential characteristic of Christian liturgy (and indeed of private prayer).

- In no meal of the early Christian era, did the president of the banqueting assembly ever face the other participants. They were all sitting, or reclining, on the convex side of a C-shaped table, or of a table having approximately the shape of a horseshoe. The other side was always left empty for the service. Nowhere in Christian antiquity, could have arisen the idea of having to 'face the people' to preside at a meal. The communal character of a meal was emphasised just by the opposite disposition: the fact that all the participants were on the same side of the table.

- A renewal of liturgical awareness, a liturgical reconciliation that again recognises the unity of the history of the liturgy and that understands Vatican II, not as a breach, but as a stage of development: these things are urgently needed for the life of the Church. I am convinced that the crisis in the Church that we are experiencing today is to a large extent due to the disintegration of the liturgy, which at times has even come to be conceived of etsi Deus non daretur: in that it is a matter of indifference whether or not God exists and whether or not He speaks to us and hears us. But when the community of faith, the world-wide unity of the Church and her history, and the mystery of the living Christ are no longer visible in the liturgy, where else, then, is the Church to become visible in her spiritual essence? Then the community is celebrating only itself, an activity that is utterly fruitless. And, because the ecclesial community cannot have its origin from itself but emerges as a unity only from the Lord, through faith, such circumstances will inexorably result in a disintegration into sectarian parties of all kinds - partisan opposition within a Church tearing herself apart. This is why we need a new Liturgical Movement, which will call to life the real heritage of the Second Vatican Council.

- The Christian faith can never be separated from the soil of sacred events, from the choice made by God, who wanted to speak to us, to become man, to die and rise again, in a particular place and at a particular time. . . . The Church does not pray in some kind of mythical omnitemporality. She cannot forsake her roots. She recognizes the true utterance of God precisely in the concreteness of its history, in time and place: to these God ties us, and by these we are all tied together. The diachronic aspect, praying with the Fathers and the apostles, is part of what we mean by rite, but it also includes a local aspect, extending from Jerusalem to Antioch, Rome, Alexandria, and Constantinople. Rites are not, therefore, just the products of inculturation, however much they may have incorporated elements from different cultures. They are forms of the apostolic Tradition and of its unfolding in the great places of the Tradition.

- Unspontaneity is of their essence. In these rites I discover that something is approaching me here that I did not produce myself, that I am entering into something greater than myself, which ultimately derives from divine revelation. This is why the Christian East calls the liturgy the "Divine Liturgy", expressing thereby the liturgy's independence from human control.

- After the Second Vatican Council, the impression arose that the pope really could do anything in liturgical matters, especially if he were acting on the mandate of an ecumenical council. Eventually, the idea of the givenness of the liturgy, the fact that one cannot do with it what one will, faded from the public consciousness of the West. In fact, the First Vatican Council had in no way defined the pope as an absolute monarch. On the contrary, it presented him as the guarantor of obedience to the revealed Word. The pope's authority is bound to the Tradition of faith, and that also applies to the liturgy. It is not "manufactured" by the authorities. Even the pope can only be a humble servant of its lawful development and abiding integrity and identity. . . . The authority of the pope is not unlimited; it is at the service of Sacred Tradition. . . . The greatness of the liturgy depends - we shall have to repeat this frequently - on its unspontaneity (Unbeliebigkeit).

- This action of God, which takes place through human speech, is the real "action" for which all creation is in expectation. The elements of the earth are transubstantiated, pulled, so to speak, from their creaturely anchorage, grasped at the deepest ground of their being, and changed into the Body and Blood of the Lord. The New Heaven and the New Earth are anticipated. The real "action" in the liturgy in which we are all supposed to participate is the action of God himself. This is what is new and distinctive about the Christian liturgy: God himself acts and does what is essential.

0 comentários:

Enviar um comentário